It’s time to take another significant step towards ensuring the smallholder farmers around the world who we all rely on for 80% of our food earn enough to sustain themselves and their families, and to invest in the future of their farms.

Purchasing the food we take for granted at ever decreasing prices, while farmers who supply it struggle to survive and maintain their farms, is not sustainable.

From the start Fairtrade was set up to address poverty amongst farmers and producers all around the world and to work to deliver them a sustainable livelihood from the crops they grow. Divine Chocolate was established not long after with that aim at the heart of its mission. Ensuring Fairtrade terms with the cocoa farmers was our start point – but we took our commitment a step further and created a new business model where those farmers owned the biggest share of the company and received both the additional finance and access to the cocoa industry that ownership delivered.

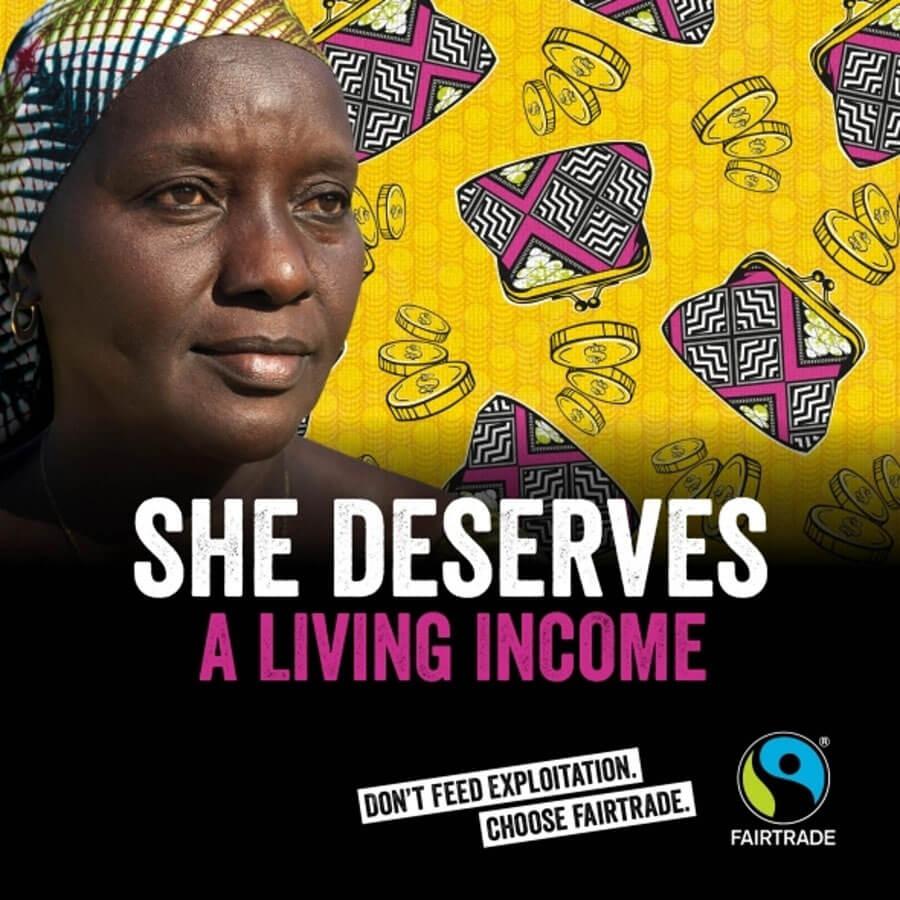

Fairtrade has achieved extraordinary things – including creating a generation of millions of consumers worldwide who have been made much more aware of where their food comes from – and that people, like them, depend on what we buy for their livelihoods. For farmers it has ensured reliable long-term trade partnerships, and some protection against the volatility of commodity markets.

Divine has led the way in the chocolate market – both engaging consumers and helping them be part of a virtuous circle where both farmers and consumers are empowered, and, as well as paying farmers the Fairtrade premium, delivering profit share, and 2% of annual income towards priority farmer-led programmes.

And yet – 25 years after Fairtrade was first established in the UK – farmers are still living in extreme poverty. The extra premium delivered with every Fairtrade transaction is not enough. It’s vital to look at what we mean by a ‘Living Income’ for farmers – and we need to reinforce our efforts to deliver it.

What is Living Income?

Fairtrade International has focused its efforts on reviewing what a Living Income really means for farmers (see more info here). If we here in the UK earned just enough to keep food on our plates, we still wouldn’t be able to pay rent, bills, for clothes – this is what we would call extreme poverty. Obviously poverty is relative - many of the things we can take for granted here – electricity, plumbing, medicines, for example – are currently are out of reach of most cocoa farmers.

We have brought these issues home to the public over the last 20 years – making people think more about the issue by asking, given the little they can earn, ‘why would anyone be a cocoa farmer?’. We have listed all the essential outgoings a farmer has to keep his or her family fed, cared for and educated, as well as keeping their farms productive and adapting to climate change, and how impossible it is to manage this on the kind of average earnings they are making.

The most recent Fairtrade report on cocoa farmer incomes in West Africa (with a focus on Cote d’Ivoire where most cocoa comes from) – shows that 58% are still living in extreme poverty, while thousands more have incomes below which they cannot reliably meet the normal costs of living and running a productive farm. The new assessment of Living Income for a typical cocoa farmer in West Africa has systematically taken into account every single element of a farmer’s outgoings, taking into account size of family, and size of farm. It looks at what constitutes a decent standard of living, labour costs (ensuring a living wage to farm workers), loan costs (usually at highly inflated rates), and it looks at if and how increased productivity will help so the farmer can sell more.

Fairtrade International has calculated that a Living Income for a farming family of eight in Cote d’Ivoire is $8965. With a good level of productivity that would mean the average farmer needing to earn $2668 per tonne of cocoa. The current Fairtrade minimum is $2000 per tonne 62% of which ($1327) gets to the farmer. Fairtrade is already in the process of raising the minimum to $2400 – this is a good step forward but is still not enough.

Why aren’t companies paying a Living Income already?

Asking major multinationals why farmers at the start of their supply chains don’t receive a Living Income has for decades produced the answer ‘the market dictates the price, not us’. They are referring to free market economics – but even on that basis this answer is somewhat disingenuous. When you are the largest players in this market – you are effectively the market, which suggests it is not something which you have no power to change.

As slaves to ‘market forces’ – where paying a Living Income does not come into the equation – multinationals have tackled their social responsibility in this area by investing directly in the sorts of things that will make farmers lives better – for example education, more rights for women – and providing tools and inputs for their farms.

But increasingly today this ‘market’ mantra is being questioned. What sort of economics are we being driven by – that apparently don’t take people and their livelihoods into account at all? Encouragingly – there are some new economic models in town that are seriously challenging an outdated system which just isn’t working. Kate Raworth’s ‘Doughnut Economics’ address the fact that “humanity’s 21st century challenge is to meet the needs of all within the means of the planet.”

What are the challenges to achieving a Living Income for farmers?

At the moment in West Africa, the ‘farmgate’ price farmers are receiving is around 62% of the Freight on Board price (FOB). For their incomes to significantly increase, either the FOB price needs to increase, meaning manufacturers paying more, or that percentage needs to go up – which is a Government decision. Just a few percent could make a real difference.

Manufacturers may well baulk at paying more – arguing that the consumer would not bear the increase. However there are undoubtedly efficiencies to be made in other parts of the supply chain – where currently there is generally a lack of transparency regarding who gets what share of the value.

Governments will also resist raising the percentage of FOB received by farmers – arguing that they need this much to invest back into the cocoa industry (and employ all their cocoa industry ministers).

How does Divine see the future?

More transparency of supply chains and an examination of competition law is going to be key – if we are to put pressure on the industry to deliver a Living Income to farmers. It is important to expose the extent of the power that major multinationals and retailers wield and how that power is becoming increasingly consolidated as these huge companies merge. Fairtrade and Oxfam are committed to keeping a spotlight on farmer incomes, supply chains and corporate responsibility in all the industries that depend on farmers and producers.

Consumer pressure will be key and it can be hard to engage people with all the technicalities and details of determining a Living Income. Divine will continue to make these issues personal – giving farmers a platform to speak directly to consumers so they can explain the challenges in their lives, and what their hopes are. Showing that the people who grow our food are like us, with many of the same fears, and aspirations – to send their children to school, to be able to hand on their business to them, to be paid on time – makes the situation real. At the same time as raising awareness amongst consumers we ensure farmers know their important role in a lucrative industry, and the value they deserve from the crops they grow.

At the recent Chocoa Chocolate Festival in Amsterdam, Stephen Ashia from ABOCFA Fairtrade coop in Ghana said a fair price is key to keeping the next generation of farmers in cocoa. He said in his country young people are still living the countryside and moving to the city because the price of cocoa is too low to continue working on farms.

Abubakar Afful, a business development advisor for cocoa for Fairtrade Africa, said the farmer is the starting point of the supply chain, without them there is no supply of cocoa.

Then he asked the audience at Chocoa: "Who in this room would switch places with a cocoa farmer?"

At Divine, we will continue to pay the Fairtrade premium on all the cocoa we buy when it goes up in 2019, as well as delivering dividends, and investing 2% of our turnover in farmer-led improvement projects that address their local issues and priorities.

We have achieved extraordinary things – but there is still a long way to go to completely eradicate farmer poverty. We’ve shown you really can run a different kind of business at scale – with farmer income at its core – and set a benchmark for the industry.